Jack Goldstone, a sociologist at George Mason University, refers to 1860s America as only our “First Civil War.” While we have not had a second American Civil War, Goldstone warns that we might now be witnessing the beginnings of it. Goldstone’s research is part of a broader picture of an intensely polarized society—one that can be seen clearly on the internet and social media platforms.

Goldstone’s opinions and research on civil wars carry weight; he’s been the expert on them for decades. According to reporting from Buzzfeed News, Goldstone was called in by the CIA to help lead the State Failure Task Force in 1994 during Somalia’s civil war and stayed on the team until 2012. The task force, a group of social scientists, worked to identify factors that predict when a nation is likely to descend into chaos. The Political Instability Task Force, as it was later renamed, predicted civil wars and democratic collapses with about 80 percent accuracy over a two-year lead time.

This model was built on by Peter Turchin, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Connecticut, to develop the Political Stress Indicator (PSI). The PSI attempts to explain how inequality worsens political instability, leading to distrust and resentment in governmental institutions. To do this, it measures factors including wage stagnation, competition between elites, demographic trends, and distrust in government.

Recently, Goldstone applied the PSI and his research on civil wars to the U.S. The research shows that the PSI is rising rapidly in the U.S., at a very similar rate to how it did before the Civil War.

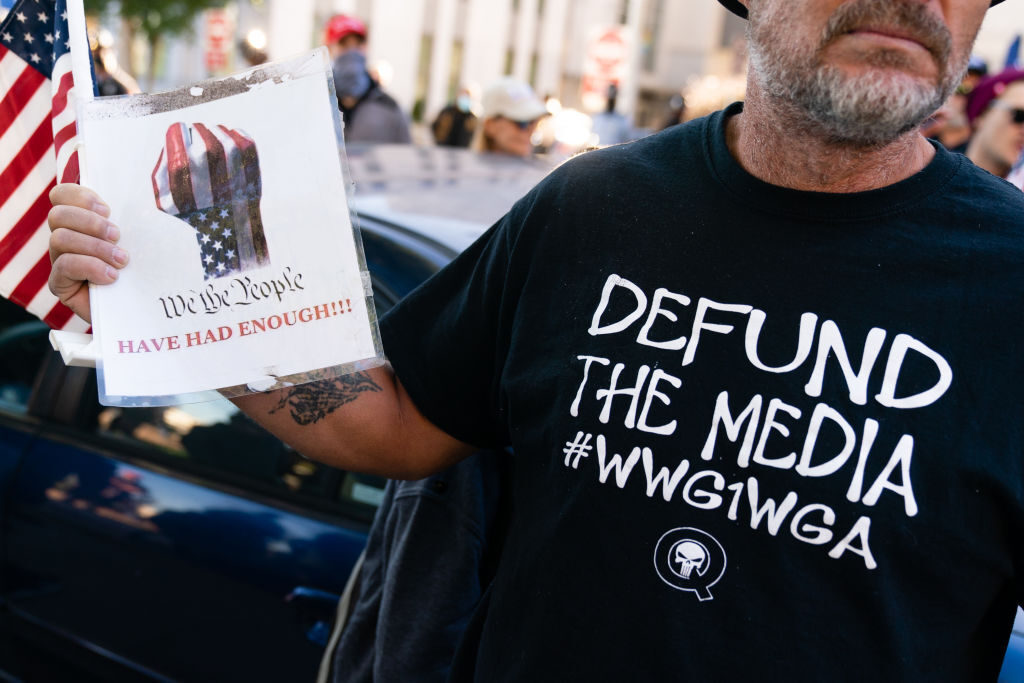

Whether or not that is where the U.S. is headed is up for debate, but considering events such as the Covid-19 pandemic, the tumultuous 2020 election, and the assault on the Capitol on January 6, it is clear that the country is showing signs of serious political instability.

The advent of the internet has accelerated the spread of information and increased global connection, which has both brought incredible progress and sparked greater instability. While the relationship between polarization and social media is complex, it’s clear that a growing segment of Americans, young and old, rely on it to inform them about the world. Whether polarized discourse on social media is a cause or a symptom of these rising tensions, what happens on these platforms will have a major impact on how Americans think about their country, the world, and each other.

Polarization on Social Media

- Affective polarization

- How much people of one party dislike members of the other party.

- Ideological polarization

- How much people disagree on issues such as gun control and immigration.

Ideological polarization, enabled by social media networks, creates a self-reinforcing system in which political divides are becoming stronger and more intense. These divides are worsened by “echo chambers” that increase the effects of confirmation bias. In other words, as people increasingly siphon themselves into their respective ideologies through personalized social media feeds, their opposition to others, such as an opposing party, continues to grow.

“Affective polarization” measures how much one party dislikes members of another. When looking at social media, this distinction from ideological polarization is important because different policy stances are not the core of the growing political divide. Our interests, from religious choices to the music we listen to, now serve as indicators of our political identification.

According to a 2019 Pew Research survey, which asked Facebook users to reflect on the data the site collects on them, most users say the site’s categorization of them is accurate. When it comes to politics, 51 percent of Facebook users are assigned a political affinity. Of those, 37 percent agree with their categorization and 14 percent say it is inaccurate.

To make this classification, the site takes into account data provided by users and their engagement with content on the site. This includes what they have posted, liked, commented on, and shared.

- Filter bubbles

- Also known as echo chambers, the phrase “filter bubbles” was coined by Eli Pariser who defines it as a situation in which algorithms skew the content we see online to favor content we like.

Facebook also gathers user data outside of the platform. Millions of companies and organizations have activated Facebook pixel on their websites, which records the activity of Facebook users on third-party websites and sends the data back to the platform. This drives users further into personalized filter bubbles, commonly referred to as “echo chambers,” in which the content is tailored to users based on these indicators.

Algorithms and Echo Chambers

Social media echo chambers are a consequence of platforms’ ideological sorting of users. In order to maximize engagement, platforms such as Facebook tend to show users content that aligns with their existing beliefs. And when recommendation algorithms suggest a new group to join or a new video to watch, they often lead to progressively more extreme versions of those existing beliefs.

In 2018, an internal Facebook report showed that the company was well aware that its recommendation engine exacerbated divisiveness and polarization, the Wall Street Journal reported. According to the article, Facebook eventually decided to ignore the findings because changes to the algorithms might disproportionately affect conservatives and could hurt engagement.

The report found that Facebook’s algorithms “exploit the human brain’s attraction to divisiveness,” one slide of the presentation read. A separate Facebook internal report from 2016 said 64 percent of people who joined an extremist group on Facebook reported finding them through the company’s algorithms.

“You have a business incentive that created algorithms that want you to stay on the site. And that means there’s a risk they will focus on negative news,” James A. Lewis, director of the Strategic Technologies Program at CSIS, said. “How do you get companies to deal with that by deliberately reducing that kind of content?”

Companies face a difficult business incentive: content that shows more extreme sources tends to get more engagement. This encourages the sharing of misleading or inaccurate news.

A study by Cybersecurity for Democracy shows that politically extreme sources tend to generate more interactions from users in the lead-up to and aftermath of the U.S. 2020 elections.

Companies are afraid that what you’ll do is you’ll switch to another platform.

James A. Lewis

Specifically, the study shows that content from sources that were rated far-right by independent news rating services consistently received the highest engagement per follower of any partisan groups. In addition, frequenters of far-right misinformation had on average 65 percent more engagement per follower than other far-right pages.

“Companies are afraid that what you’ll do is you’ll switch to another platform,” Lewis added.

Altering the Algorithms

Understanding the realities behind these algorithms and how they exacerbate polarization is nearly impossible as these patented recommendation engines are increasingly categorized as opaque “black boxes.” As social media giants get larger and their algorithms become more powerful, better understanding of how these companies function may offer viable solutions.

As social media companies have come under increasing public and government scrutiny, they have sometimes responded by making changes to the way their platforms function. For example, Facebook has made a number of changes to their news feed, including one highly publicized rework in 2018 that tweaked the news feed algorithm to show more posts from friends and less content from publishers and businesses. The stated intention of this change was to encourage “meaningful interactions” among its users.

If this change had been intended to blunt the impact of divisive content and filter bubbles, the evidence suggests that it did not succeed. A study by the Nieman Journalism Lab showed that divisive political content remains widespread. And critically, for Facebook, its users were more engaged with divisive content than ever.

Twitter has also attempted to combat polarization and misinformation by cracking down on the use of bots and other fake accounts, which have played a major role in spreading this content. According to the Washington Post, Twitter suspended more than 70 million such accounts over the course of just two months in 2018. The newspaper characterized this as a major change in approach for Twitter, which had spent years opposing such crackdowns.

Twitter’s compliance with calls for reform is an encouraging sign, but the form this compliance takes leaves something to be desired. In April 2021, Twitter announced its “Responsible Machine Learning Initiative,” which promised to scrutinize not only the algorithms that drive content recommendations but also the other ways their algorithms contribute to bias. However, they admit that the “results of this work may not always translate into visible product changes, but it will lead to heightened awareness and important discussions.”

It remains to be seen if this program will yield tangible results or whether the public will be able to access any evidence of change. Another question is whether Twitter will ever be willing to share the inner workings of these algorithms with the public. Whether the mechanics are ever made public, internal changes to Twitter's algorithms and policies have had a major impact on communities on the platform in the past, such as Black Twitter.

Transparency is a common theme in the public statements of social media companies such as Twitter, but it has generally been hard for them to put into practice. The algorithms at the root of these problems with polarization are also the key to the continued engagement of their users, and therefore to their profits. This makes companies reluctant to disclose how they function or to alter them in a way that could reduce engagement. But as government interest in these issues increases, so do the odds that companies could find themselves forced to change course.

The Role of Government

In recent years, social media companies have faced increasing scrutiny from Congress. However, proposals for government intervention vary widely, as do the motivations for such intervention.

Some U.S. lawmakers—particularly conservatives—are concerned that social media companies have too much power over speech on their platforms. Others are more interested in compelling companies to control the spread of misinformation more aggressively.

Curiously, both groups have at times rallied around the same proposal: amending Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. This law has shielded social media companies and other platforms from most legal liability over content posted by their users. While controversial, the law is a foundational piece of the modern internet’s legal status, and there is little consensus on how it could be replaced.

Others have proposed that the government could instead compel social media companies to give users more control over what they see in their feeds and more transparency into how platforms are enforcing their rules. Tom Johnson, former general counsel to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), argued that these approaches may have a better chance of making a positive impact.

“The advantage to these sorts of proposals, while far from perfect, is they’re focused on transparency, focused on consumer protection, focused on tailored enforcement action. These things, I think, have the best chance of being upheld in court. They’re neutral,” Johnson said.

Even if the government changes its regulatory approach to social media companies, it would be unlikely to affect all platforms across the board. According to Johnson, some people advocate focusing any regulatory changes on the biggest platforms. “There are some policies out there that say ‘let’s make the large providers common carriers, because they can absorb the regulatory cost of that, and those look more like public fora. Let’s allow experimentation to occur at the level of the small providers.’”

This kind of experimentation has already been occurring on social media platforms, large and small. By looking at approaches that have worked in newer and smaller online communities and learning from the latest research on how social media interacts with human psychology, there may be new opportunities to address these problems more effectively.

A New Structure for Social Networks

While Facebook’s strategies to combat polarization have seen mixed results, there’s no shortage of fresh ideas on how to combat polarization.

Some believe that if social media companies were to require proof of identity and age for every user account, people would feel less shielded by anonymity, and therefore less likely to engage in polarizing activity. There appears to be sparse data backing this up, however. Another idea is to alter algorithms so that they no longer select for content that triggers intense emotional responses.

One particularly interesting proposal focuses on a specific part of how the major social networks are organized. A study by researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, Northwestern, and George Washington University found that the formation of insular groups or echo chambers did not itself cause or exacerbate polarization—“influencers” did.

Many of us have a particular image that comes to mind when we hear that word, but influencers are any social media account with a large number of followers. Influencers tend to act as central nodes within the network of an echo chamber, and when they engage in highly polarizing behavior, it spreads out to the rest of that echo chamber’s population.

When researchers in the study divided users into ideological echo chambers without an influencer, those users became less polarized on average. This is because, according to at least one researcher involved in the experiment, decentralized, egalitarian networks spread ideas based on their quality—not the person touting them.

Bottom-Up Changes

Users have also attempted to find their own solutions to the problems of online polarization. In some cases, that has meant abandoning the major platforms altogether for new, differently organized competitors.

Many of the things we talk about are really symptoms of larger social problems, and treating the symptom does not cure the larger social problem.

James A. Lewis

One example was a series of decentralized networks called the Fediverse. The most popular, Mastodon, was billed by some as an alternative to Twitter that would be free of the platform’s most divisive elements. But Mastodon soon found itself faced with many of the same problems that had driven its users off of Twitter, including a mass migration from the far-right social media platform Gab. Suddenly, the decentralized format was more of a hindrance in dealing with the newly-present Gab users because Mastodon couldn’t create platform-wide regulations.

The story of Mastodon highlights that the problem of polarization is bigger than any one social media platform. “Many of the things we talk about are really symptoms of larger social problems, and treating the symptom does not cure the larger social problem,” Lewis said.

Researchers at the Polarization Lab at Duke University have tried to give social media users tools to better understand the way that the platforms are shaping their perceptions. While they claim promising results from some of their early studies, their efforts are still akin to swimming against the current on platforms that are pushing their users in a very different direction.

Despite widespread issues with social media polarization, many users have still found spaces that foster supportive community and honest dialogue, both on the largest platforms and their smaller competitors. While these users often feel that they are working against the platforms they use and the algorithms that drive them, their successes can still offer lessons for the ways platforms can create more positive interactions between their users.

Debbie “Aly” Khaleel is the content creator and community manager of Noir Network, a network for Black femmes in content creation. Khaleel says that she wanted to create a nurturing environment with other content creators within the community.

“We’re all like brands, essentially, we’re all business owners or entrepreneurs, and I wanted to treat them with that same regard and respect,” Khaleel said.

Community spaces such as the Noir Network facilitate community engagement that helps users within that community feel safe and build connections with other like-minded users. The creation of smaller social network spaces, however, does not fix the larger social issues of polarization online. What these spaces do is create a safe space for users with specific interests, even though these spaces still exist within the greater problem of ideological polarization on social media.

Ultimately, the largest platforms will need to find ways to combat polarization and extreme content—with or without government intervention.

While the approaches that have proven effective on smaller platforms and in smaller communities may not scale up, there may still be lessons to be learned from the experiences of these communities. They can also serve as a reminder that the internet is not entirely defined by the corporate policies of Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube. Existing alongside the algorithm-driven filter bubbles are still communities built on trust, accountability, and common purpose.