Last spring, Chiara Zambrano spent 10 nights on a small wooden boat on the Scarborough Shoal—120 nautical miles west of the Philippines in the South China Sea. She was there to report for ABS-CBN, a Philippine television network.

The 150-square-kilometer coral structure involves a territorial dispute between China, Taiwan and the Philippines. It was the site of a standoff in 2012, when Filipino forces tried to arrest Chinese fishermen who were poaching inside the reef. Eventually, Beijing took control of the coral from Manila.

But there is another dimension to the tensions here. When Zambrano and her crew visited the shoal, they saw at least 12 Chinese fishing boats around the reef.

The small ships equipped with cranes were used to harvest giant clams from the sea—a destructive process that dredges up coral to poach the endangered species. The Chinese fishermen pumped air into the coral, crushing it to clear the sand and reveal the shells of clams.

“Can you just imagine? The Scarborough Shoal stands no chance against that much poaching, that much destruction,” Zambrano said.

A Filipino fisherman told Zambrano that at the rate the shoal was being destroyed, he doubted his children would be able to see it. His concern about the fate of the South China Sea’s ecosystems is not an overreaction—experts and residents agree that an environmental catastrophe is at best possible, and at worst inevitable.

The Damage Done

The South China Sea is home to some of the highest marine biodiversity in the world. There are hundreds of islands and islets with 571 known species of reef corals, though the actual number could be much higher. It’s a pathway for migratory fish, like tuna, which travel through the sea and feed on larvae in the reefs.

In turn, the South China Sea provides food security and is critical for the economic livelihoods of many—around 3.7 million people work at fisheries in the sea. Many more unofficially work in the region. This body of water accounts for more than 50 percent of the world’s fishing vessels.

Vietnam’s total catch, based on both reported annual data and estimated unreported catch, has increased rapidly, especially since 1993. Data from Sea Around Us.

However, overfishing, artificial island-building and giant-clam poaching threaten marine ecosystem health. The reefs have been declining by 16 percent per decade, and that rate has been accelerating over the past five years.

The Philippines saw a huge jump in total catch, based on both reported and estimated data, in 1996. Since then, the Philippines has remained at a higher average for annual catch. Data from Sea Around Us.

“It’s a matter of a few years, not a few decades, before the South China Sea is no longer productive enough for anybody to make a living off of,” said Gregory Poling, a senior fellow for Southeast Asia and director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS).

Since the 1950s, fish stocks in the South China Sea have dropped by over 70 percent, and during the last 20 years alone, catch rates have decreased over 65 percent.

For fishermen in Vietnam and the Philippines who rely on the South China Sea’s repositories of marine wildlife, its depletion will be generationally devastating.

“There’s going to be more and more consequences. Kids are not going to go through school because they’re picking up food. And that reduces their occupation mobility,” said John McManus, professor of Marine Biology and Fisheries at the University of Miami.

Since 2014, China has built seven artificial islands within the South China Sea, helping to bolster its claims. The dredging involved in these extensive construction activities prevents the reef from receiving adequate sunlight. More than 15,000 acres of reef have been severely damaged or destroyed as a result.

Beijing insists that these projects have only impacted dead or damaged reefs, but experts are convinced that they have made the situation dramatically worse.

“The patient was sick, and they buried it alive,” McManus said.

While artificial island-building has destroyed a considerable amount of coral, the poaching of giant clams by Chinese fishermen has proved to be the most harmful. Using propellers mounted on small boats, these fishermen engage in intense prop chopping, which causes massive scarring of reefs.

And as reefs deteriorate, fish in the South China Sea have less to eat and fish stock rapidly declines. An additional 25,000 acres have been damaged from destructive clam digging practices.

“If stocks collapse, they’re going to be out of work, their families are going to go hungry,” Poling said. “It’s going to be an enormous burden on social safety nets that don’t have a whole lot of extra space right now.”

Ninety-nine percent of fish catch is in a country’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), indicated by the colored lines.Conducting fish stock assessments is nearly impossible. The combination of officially reported catch and reconstructed estimates, is the most accurate representation of overfishing.Thailand, China, Malaysia, Taiwan, and the Philippines’ data includes fish catch from neighboring seas like the Gulf of Thailand. Sources: Sea Around Us, Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

The Geopolitics of the South China Sea

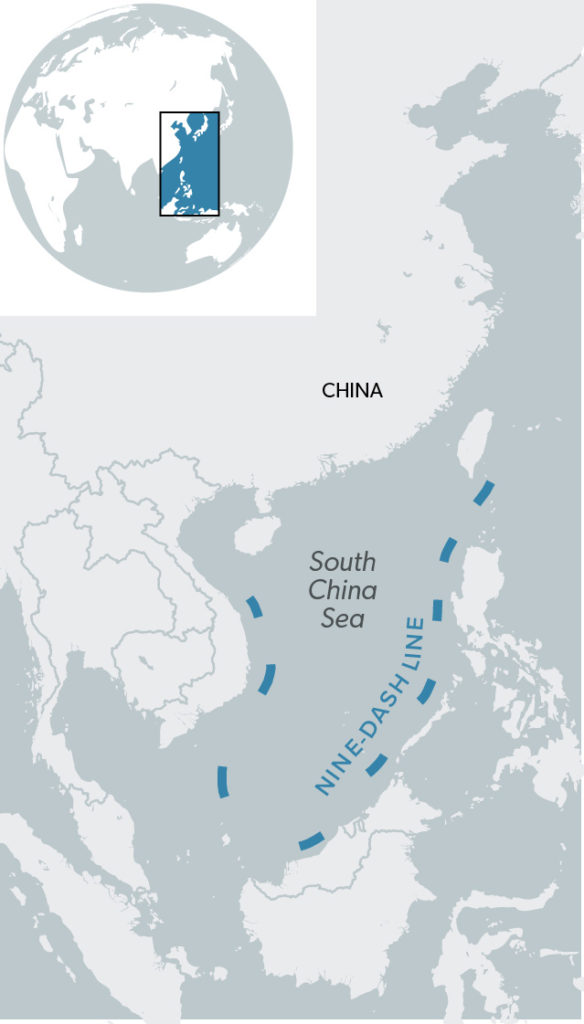

The struggle to protect the rich marine biodiversity cannot be separated from the geopolitical conflicts in the South China Sea. Seven parties lay overlapping claims to the waters, including China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Taiwan and Brunei. According to the 1982 United Nations Convention Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the area within 12 nautical miles of a state’s coastline is considered territorial sea, or sovereign territory. States are entitled to an exclusive economic zone (EEZ), with rights to all economic resources within 200 nautical miles of their coast.

However, China asserts its “historic rights” to nearly 90 percent of the South China Sea, overriding the jurisdiction of most of the EEZs in the region. China’s ambiguous claim is known as the nine-dash line, which an international tribunal ruled illegal in 2016.

Taiwan’s role in this dispute is especially complex. Though Taiwan officially calls itself the Republic of China, Beijing considers it a renegade province, and most of the world’s countries do not recognize it as an independent state. However, it exercises de facto autonomy. Taiwan claims all the the rocks and reefs of the South China Sea, but has distanced itself from China’s more expansive claim to “historic rights” over waters and seabed.

Although UNCLOS mandates that states should cooperate with each other, there are no enforcement mechanisms. The Chinese continue to prevent other countries from fishing or other operations well outside of their own EEZ, creating conflict with other claimants. The United States runs military exercises and freedom of navigation operations through the South China Sea, but has done little else to challenge China’s claims.

In the meantime, Beijing has been engaging in gray zone tactics, intimidating others without crossing the threshold to provoke an armed conflict. China, for instance, has flooded the sea with fishing vessels operated by former People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy commanders or members of the maritime militia in order to create an intimidating presence and harass smaller claimant ships. Keeping activities below the level of military force, the Chinese government can impose its will and dodge international scrutiny.

The Looming Danger

Most of the large Chinese fishing operations—taking place over 1,000 miles from the Chinese coast—aren’t even profitable. But Beijing sees them as part of a strategy to assert its maritime claims, and subsidizes the operations heavily. These fishing vessels, guarded by the China Coast Guard, are drawn primarily by government subsidies that pay for them to be there as a marker of China’s claims.

“They might be getting paid to go down and fish, and sometimes they’re getting paid to provoke Vietnamese boats. Either way, they’re getting paid,” Poling said.

The presence of these subsidized Chinese fishers—who account for the largest share of fishing in the area—has dramatically accelerated the decline in fish stocks.

“Most of what we see [in China] are heavily state-subsidized commercial fisheries, and if stocks collapse, the state will just subsidize them to do something else,” Poling said. “China will be inconvenienced, and Southeast Asian communities will be devastated.”

But McManus says China has been reluctant to let outside scientists conduct fish stock assessments, leaving the international community partially blind to the scope of the problem.

“It could be cascades [of collapses] and we wouldn’t even know. We think it’s already happening, but we don’t have any good records,” McManus said. “For scientists or anybody to do anything there, it is very difficult because they’re not in a position to give up their lives.”

Rising Tensions

The looming economic consequences of declining fish stocks, and the dangerous and provocative methods that Chinese vessels have employed to deter other claimants from fishing in the South China Sea, have provoked a backlash in the region.

China will be inconvenienced and Southeast Asian communities will be devastated.

Gregory Poling

Le Hong Hiep is an expert in Vietnamese studies at the ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. He says there is a strong sentiment among the Vietnamese about defending Vietnam’s sovereignty and economic interest in the South China Sea. Hiep says China asserting their jurisdiction unilaterally, sometimes through violent means, creates resentment towards the country among Vietnamese fishermen.

“The Vietnamese government and the Vietnamese fishermen want to protect the resources. Vietnamese fishermen are now at the forefront of Vietnamese resistance to Chinese expansion,” he said.

There are concerns that China’s increased capacity to patrol the sea, thanks to access to the artificial islands and the ramp-up of its naval reach, would prompt Beijing to scale up its assertion of maritime claims. But McManus observes that Vietnamese and Filipino fishermen would continue trying to make a living, no matter what. “People are so desperate for that little bit of income that they’re going out there,” he said.

But Filipino fishermen who venture into these waters take on great risk—Chinese vessels have sunk Filipino fishing boats in what are widely seen as intentional hit-and-runs. Fishermen’s rights groups in the Philippines and Vietnam have protested against Chinese usurpation of the waters.

One Filipino group, Pamalakaya-Pilipinas, says some fishermen are too traumatized to return to the sea after facing harassment by the Chinese paramilitary forces. A public information officer for the group, Jam Pinpin, says this creates a twofold dilemma. The former fishermen often can’t make ends meet or put food on the table, and because the fisheries are depleted, other Filipinos also struggle with food insecurity.

“[The South China Sea] contributes greatly to our food security. When China continues to destroy it and it deteriorates, it will affect not only the lives of the Filipino fisherfolk, but also our local food supply and local food security,” Pinpin said. “The Chinese occupation does not only concern our sovereignty and territorial integrity. It also concerns the environment and marine resource[s].”

Course Correction

With claimants wrestling for control in the South China Sea, the damage to its already fragile ecosystem is often overlooked. But experts say cooperation between China and its neighbors on environmental issues may be the only path toward preventing ecosystem collapse and could reduce tensions in the region.

China’s unilateral efforts towards environmental protection have not proven to be effectively implemented or fairly enforced. China recently launched the Blue Sea 2020 campaign to “enhance marine environmental protection” in the South China Sea. Poling, however, thinks this is actually a proclamation that China will enforce its annual fishing ban on other claimants more aggressively. He also sees the project as a chance to bolster nationalism at a time of political sensitivity because of Covid-19.

Multilateral efforts have been made to shore up environmental initiatives and get China involved. At the 2017 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit in the Philippines, all member countries and China signed a Declaration for a Decade of Coastal and Marine Environmental Protection in the South China Sea. But Poling says it was more aspirational than concrete, and though they were supposed to have follow-up discussions, they have yet to take place.

Legal mechanisms exist to weigh in impartially, and in some cases have emphatically rejected China’s claims to historic rights over the South China Sea. A 2016 tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration said the country violated international law by damaging the marine ecosystem and endangering Filipino ships.

But the international mechanisms of enforcement often lack teeth. China has rejected the tribunal’s 2016 ruling, asserting that the tribunal lacked any jurisdiction over the issue.

James Kraska, professor of International Maritime Law at the U.S. Naval War College, says that international courts are much like a speed limit on a backcountry road. Although the speed limit may not always be followed, it does set a baseline for those traveling on the road.

“Most nations comply with most international law, most of the time,” he observed. The rulings of international courts, even if they are not binding, make it more difficult for China to act with impunity in the South China Sea.

But to really save the South China Sea’s ecosystems, China must work with the smaller claimants. Without multilateral cooperation it is impossible for environmentalists and researchers to get an accurate stock of the resources left in the sea.

“The stone that has to get pushed to start an avalanche is that China has to agree to do this multilaterally,” Poling said. “China has to agree to establish a fisheries management regime with ASEAN. . . The fish move regardless of arbitrary international boundaries. There has to be cooperation.”

No Easy Answers

But even a united front among the ASEAN claimants is easier said than done. Each country has complex relationships with one another and with China. Often those relationships and alliances can change from one government to the next.

“There’s a very low probability of [meaningful cooperation] happening within Southeast Asia because these countries have a mutual suspicion and a history of not really working together effectively on anything other than broad economic principles,” said Bonnie Glaser, a senior adviser for Asia and director of the China Power Project at CSIS.

And the United States is in an especially tricky position. It would like to see a South China Sea where China respects international maritime agreements. But because it has no territorial claims in the region, getting involved presents significant hurdles.

The fish move regardless of arbitrary international boundaries. There has to be cooperation.

Gregory Poling

Currently, the United States conducts freedom of navigation operations, or FONOPs, with its Navy through the sea. Some experts suggest that it needs to get tougher on China’s behavior. Kraska says as many avenues as possible should be considered, including sanctions or even restrictions of China’s freedom of movement near U.S. territorial seas. But any intervention must be weighed against the risk of provoking an armed conflict with China.

“My expectation is that the United States will continue to rhetorically condemn the bullying and intimidation, but is unlikely to intervene because of its neutrality [on sovereignty disputes],” Glaser said.

Cooperation for Conservation

Most experts agree that public opinion both on an international stage and within China’s borders can be a potentially effective tool for slowing China’s aggression in the South China Sea.

McManus believes the most promising course of action for improving relations is what he calls a “peace through conservation” approach. He suggests that sustained focus on the environmental challenges in the region, both within China and globally, could build the basis for cooperation not only on environmental issues, but even more broadly.

“There is no shortage of conservation-oriented people in China. People risk their lives to protect wildlife in China, we just have to build on that,” McManus said. “That’s true of all the countries and get [conservationists] to dominate the issues as opposed to, ‘Oh, they’re stealing our property.’”

Poling agrees that there are many Chinese who care about the marine environment, but he cautions that “they’re not setting policy in Beijing.”

As China ascends as a global economic force, it also desires to consolidate its sphere of influence and be seen as a leader in the region and globally. This might incentivize Beijing to take environmental sustainability seriously.

“If Beijing becomes convinced that unilateral efforts that destroy the marine environment are undermining that effort to be seen as a leader, then Beijing might very well decide that it’s political aims are better served by being a good maritime steward,” Poling said.

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all agreement to the disputes, especially considering the lack of outcry from the international community. However, the deteriorating ecosystem could serve as an entry point to further cooperation between claimants.

“Certainly, the role of marine conservation and fisheries management is an on ramp to a whole lot of other cooperation,” Poling said. “If states can show that they can cooperate in one area, presumably it builds momentum that can be used in others, and that’s what’s desperately needed.”