On March 2018, Hungarian public broadcaster M1 ran an interview with a woman named Natalie Contessa—a dual citizen of Hungary and Sweden as she told M1. After 40 years of living in Sweden, she said that immigration had changed the place, and she was now avoiding the metro for fear of getting harassed by Muslim immigrant men. She was moving back to Hungary because she no longer felt safe in Stockholm, she said.

However, a few weeks later, the Hungarian news website 444.hu discovered that the facts of Contessa’s story didn’t add up. The website found that Contessa herself had arrived in Sweden as an immigrant and since 2015, had been convicted of several crimes. The 444.hu website also discovered that there was no indication that Contessa had ever lived in Stockholm. The M1 interview, however, continued to run the video throughout social media.

By the time Facebook deleted the video, it had garnered more than a million views.

The story came at a precipitous moment as Europe wrestles with an intractable migration crisis while the media grapples with the surge of disinformation emerging from the crisis. The story went viral a month before the Hungarian parliamentary elections—an election that was looking increasingly like it would favor the Fidesz-KDNP (Christian Democratic People’s Party) alliance, led by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his anti-immigration platform. The news website 444.hu’s story emerged as Hungary’s media outlets were increasingly pressured or bought by those close to Orbàn’s Fidesz party. By 2017, Fidesz or Fidesz allies had gained control of all media in Hungary.

“Massive migration goes together with the increased terrorist threat,” Orbán said on the eve of the election. “When there is large migration, women are under threat of violent attacks.”

On April 8—election day—the Fidesz-KDNP alliance won a resounding victory. It gained 133 seats out of 199: a supermajority.

Europe’s refugee crisis has remained a divisive political issue, and one that an increasing number of European leaders have leaned on to bolster public support for tighter immigration policies and populist causes. It has generated an alarming number of false news stories that are disseminated across social media—and sometimes across mainstream media, rattling public trust in the press and jeopardizing the legitimacy of newsrooms across the continent. Fake news has proven to sway public opinion—a concern experts and media monitors fear will play heavily ahead of this year’s European parliamentary elections in May.

While governments remain alert, the resiliency of democratic values and institutions are being tested as efforts toward a comprehensive strategy to contain or regulate disinformation are being met with hurdles.

Firehose of Falsehoods

Propaganda, disinformation, and fake news have existed in societies around the world for hundreds of years, but the advent of social media has magnified their potential to reach more eyes and inundate audiences with frequent and repetitious messaging. In 2014, the World Economic Forum identified the rapid spread of misinformation online as one of the top 10 trends in modern societies.

Seth Jones, director of the Transnational Threats Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), says the speed and volume at which fake news is disseminated degrades the ability to tell fact from fiction.

“[Migration] has been the gasoline for the disinformation fire,” Jones said.

Other European countries have taken a page from Hungary’s playbook in promulgating false narratives about migrants.

In Italy, Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini, a Eurosceptic and head of the right-wing then-Lega Nord party, capitalized on a fake news story about a 9-year-old Muslim girl in Padua, a city in northeast Italy. She was said to have been hospitalized after being sexually assaulted by her 35-year-old husband.

Τhe story was released in November 2017, and several major news outlets reported on the alleged incident. Before the story was officially denied and newspapers retracted the story, it was shared by several affiliates of Lega Nord and by Salvini.

On Twitter, Salvini, wrote:

Padua, nine-year-old girl given in marriage to a 35-year-old man was hospitalized for the bleeding caused by the sexual violence.

ALL THIS IS HORRIFIC.

We don’t have room in Italy for all this “multiculturalism”!

The post was later removed from Salvini’s Twitter and Facebook profiles. But the story brought immigration to the forefront of the March 2018 general election. Salvini’s Lega won 17.69 percent of the votes—giving a boost to the far-right anti-immigration coalition.

According to a recent poll, two-thirds of Italians do not want more immigrants, fearing they will take away jobs and increase crime.

David Kaplan, executive director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network, says some far-right political parties have weaponized fear and confusion to create an environment where the truth is put on trial.

“They want to confuse things so badly that people don’t know what is true and what is not,” Kaplan said.

Terms of Engagement

Today, the internet has not only vastly changed and increased the volume and variety of news available to citizens but has also profoundly changed the ways citizens engage with news.

According to the European Commission, social media and search engines were the main ways people consumed their news for 57 percent of social media users in the European Union (EU) in 2016. While traditional media compete in this space, some warn that it is only a matter of time before “deep fakes,” or disinformation that will be indistinguishable from real reports, will challenge legitimate media outlets.

Thomas Miller, an adjunct professor at the School for Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University, observed that the internet has removed barriers to entry and the perceived necessity for newsmakers who act as gatekeepers.

“With the internet, you can spread information incredibly cheaply and quickly, and you don’t have to have the resources that one would have had before,” Miller said.

If you can separate citizens from institutions, their susceptibility grows.

CSIS’s Jones noted that this leaves populations further vulnerable to fake news, degrading the perceived need for news institutions and the fourth estate.

“If you can separate citizens from institutions, their susceptibility grows,” Jones said.

The case of distrust towards both the media and European institutions, as shown in the 2018 recent Eurobarometer, seems to be recovering, compared to periods before the financial crisis. However, the levels of distrust are still high, while the amount of trust varies across the continent, with Europe’s south holding the lowest numbers.

Heather Conley, director of the Europe program at CSIS, notes that fake news has helped to craft a counter narrative that injects skepticism about the EU as a unified and effective body.

“The counternarrative is being led by Mr. Orbán and Interior Minister Matteo Salvini, meaning that Europe—the EU—is no longer able under its current format to be able to manage Europe’s challenges—particularly migration,” Conley said. “They want to create a different EU.”

“Now, what’s unclear is that citizens believe that this is their future.”

A Four-Pronged Approach

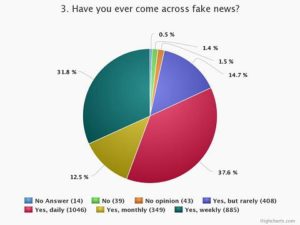

In Europe, voters are aware of the dangers of disinformation, but how to address it is a different story.

According to the European Commission, some 83 percent of Europeans consider fake news a threat to democracy. While efforts at combatting disinformation have begun in earnest, they are multi-pronged and require a full societal effort.

Last December, the European Commission launched an action plan that includes four major pillars. The first suggests marrying both fact-checking and collective knowledge, along with optimizing the EU’s monitoring and detection capabilities. The second recommends boosting online accountability. The third recommends raising awareness by fostering education and media literacy. The fourth suggests engaging the private sector to tackle disinformation.

The action plan specifies that various measures should be taken by countries and the EU at-large, placing a special emphasis on measures that should be adopted by digital platforms in order to limit disinformation.

Last May, members from all facets—the EU, private industry, and the press—came together in Madrid for a conference on fake news.

In attendance were representatives from the social media industry, including Facebook and Google, MEPs from major European political parties, and eight editors-in-chief from the Leading European Newspaper Alliance (LENA) newspapers—EL PAÍS, Le Figaro, Le Soir, Die Welt, Gazeta Wyborcza, La Repubblica, Tages-Anzeiger, and Tribune de Genéve.

Spanish MEP Maite Pagazaurtundúa, a panelist at the conference, noted that legislation has not kept up with the post-internet realities, and should be reexamined.

“The ecosystem has changed, and if we don’t adapt to face it, we will have failed.”

The European Commission has also proposed the establishment of a Network of Cybersecurity Competence Centre. With cooperation from member states, the network would coordinate cybersecurity-related financial support from the EU’s budget and to guarantee that Europe is provided with state-of-the-art systems.

Last October, Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Mozilla as well as the trade associations, both representing online platforms and the advertising industry, agreed on the guidelines as proposed by the Commission and signed the Code of Practice.

Google has announced it will publicize the identity of organizations paying for political ads, during the 2019 European parliamentary elections. As a result, any advertisement, published by a political party, candidate, or officeholder will have to clearly state to the users who paid for it.

Google is also introducing a new process to verify these identities. A similar initiative was announced by Facebook. These are steps towards making online political advertising more transparent.

The Way Forward

Outside of Europe, newsrooms are also contending with the threat of fake news as a major threat to democracy.

“There is no democracy without a free press,” said Martin Baron, editor in chief of The Washington Post. He noted that newsrooms can create fact-checking verticals and incorporate them into stories with complicated and contested narratives.

“Over time, people will know what is the truth.”

Over time, people will know what is the truth.

Tom Hamburger, an investigative reporter with the Post, added that the media should offer clear explanations of their process and how they go about reporting the truth.

“Disinformation can be beaten only with transparency and by giving wider publicity to these efforts.”

What remains to be seen is whether these new measures will be enough to root out and stop the spread of fake news stories such as in the case of Natalie Contessa. A more pessimistic view would maintain that at the root of this phenomenon lie deep rifts within European society that must be reconciled for a way to be seen forward.

Last December, Hungary’s Orbán was called out by European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker after a leader’s summit in Brussels.

“I made it very clear to the European Council that some of the prime ministers sitting around there, they are the origin of fake news,” Juncker told reporters. “When he’s saying that migrants are responsible for the Brexit: fake news.”

What is clear is that if these efforts fail there could be much wider and troubling implications for the health of European democracies.